I specialize in the study of oceanic vortices, focusing on mesoscale and submesoscale eddies (with an horizontal extent between 1-100 km) and their critical role in ocean circulation, climate, and tracer transport. My work combines satellite altimetry, in situ observations, and numerical modeling to study the dynamics, interactions, and impacts of these eddies—with a particular emphasis on high-latitude and polar regions.

Satellite Altimetry

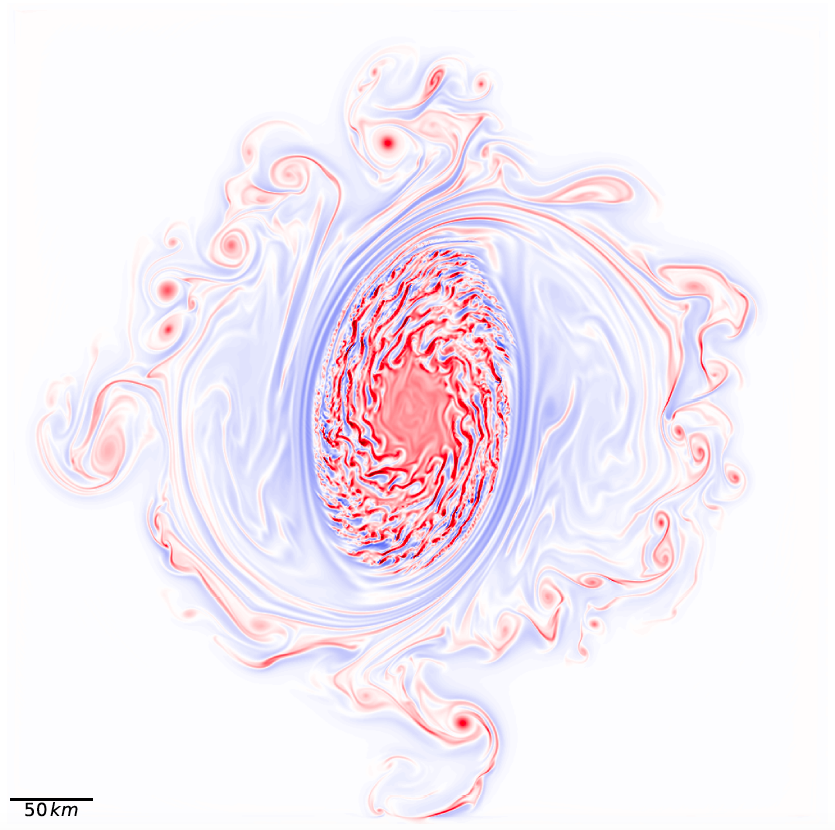

Satellite altimetry, in particular the new SWOT mission, provides synoptic, high-resolution measurements of sea surface height and derived geostrophic currents. My work leverages these data to track the life cycle of eddies, from formation to dissipation, and to analyze their interactions with surrounding flows. This approach has revealed previously unresolved features, such as eddy shielding, secondary instabilities, and dipolar interactions, offering new perspectives on the dynamics of mesoscale and submesoscale processes.

Numerical Simulations

Numerical models serve as a critical tool for exploring the physics of oceanic vortices under controlled conditions. I use several kind of numerical models (from 2D Quasi-Geostrophy to Large Eddy Simulations) to simulate eddy dynamics, testing hypotheses about their generation, stability, evolution, and response to environmental factors such as stratification and topography. These simulations complement observational data, allowing us to isolate mechanisms and predict behaviors that are difficult to capture in the field.

In Situ Observations

Direct measurements from gliders, moorings, and research vessels provide essential ground-truth data for validating satellite and model results. From data collected during field campaigns, measuring eddy structures, their vertical extent, and their interactions with the surrounding ocean, I refine theoretical models and ensure that satellite-derived interpretations accurately reflect real-world processes.